Stories are the answer

Early morning on December 20, 2016, I found my way into a huge sports field at MIT, plagued with evenly-spaced tables ready for an exam. Nervous, as if I were back to school, I was the first one to get there. Our professor would get there a bit later—that was Patrick Henry Winston.1

Three months earlier, on September 7, 2016, I would attend what was the first of a series of lectures of Winston's introductory course to artificial intelligence—6.034—and would sit in the first row of Huntington Hall2, room 10-250, colloquially known as "Ten Two Fifty," located right below the Great Dome3 of MIT.

Some days, I'd arrive early and get a chance to talk to Patrick for a bit before class. What's the most dangerous power tool you've ever used? He asked me one day. Silence. I didn't know what to answer. I thought an architect would have used power tools. He followed. I was pleased to see he knew my name just a couple weeks into the course. In retrospect, I find most of my "tools" these days being virtual pieces of software.

In one of those classes—as if it were a line from Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy's Westworld series (2016)—Winston emphasized the relevance of the following question: Can you explain why you think so?

To Winston, whether a machine is able to answer questions of the type of why and how it reached a conclusion in a humanlike way was as important, or even more, as the conclusion or the answer itself.

"Genesis supports steps toward story understanding," reads the headline of his draft paper with Dylan Holmes, titled The Genesis Manifesto: Story Understanding and Human Intelligence4 as of December 13, 2016, barely ten days after the release of HBO's series first seasons' finale. "To understand what makes humans uniquely intelligent, we build computational models of how humans tell and understand stories."5

A system like Genesis is meant to be on top of all other technologies and make the system self-conscious. Genesis can understand stories, answer questions, and—unlike other narrow artificial intelligence systems6—reason and explain why it reaches its conclusions.

Winston shared a fascinating (yet worrying) idea in class. If you don't know how a program gets to a conclusion, you can't trust it. It's not possible to debug it. As a matter of fact, we rarely know how machines work, but we still give away our trust for their convenience.

Three years ago, on April 20, 2017, I met with Patrick to ask for his feedback on the project I was working on at the time—Suggestive Drawing7. He tested one of my first working prototypes, a drawing app running on an iPad with an Apple Pencil.

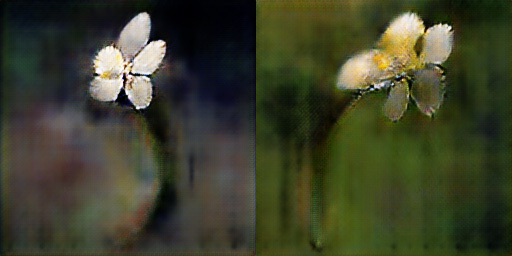

Patrick sketched these two flowers.

Patrick Henry Winston's free-hand flower sketches. Timestamped at April 20, 2017, 15:28.

A few seconds later, the system returned a prediction for each of them using a generative machine learning model that only knew about daisies.

Pix2Pix predictions using Patrick's flower sketches as input with a model trained to learn a mapping from line sketches of flowers to daisy flower photo textures.

Output processed with an alpha mask.

That's pretty cool! Patrick said. We discussed the project for half an hour and I left his office at Stata Center.

That was the last time I saw him.

Patrick passed away on July 20, 2019. His memorial8, held in October 2019, surfaces the fact that Patrick influenced many people's life in profound positive ways. Not only as a teacher or a mentor, but as someone who loved sharing the experience he acquired over years of teaching.

I never had a chance to interview Winston for the podcast, but I'd have loved hearing more about his worldview. Luckily, he contributed a great amount with numerous online lectures, talks, and other learning resources.

There's a sentence that Patrick said that will stick with me for the rest of my life.

Stories are the answer.

Patrick Henry Winston (1943-2019) was the Ford Professor of Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). I invite you to watch his Hello World, Hello MIT talk (2019) to learn more about his worldview and his contributions, and to Watch his 6.034 lectures online. ↩

The 10-250 Lecture Hall is one of the most popular meeting places in MIT. ↩

The day I sketched this view was the day I met Pier Gustafson for the first time. He showed up biking across Killian Court, right in front of the building that was named after MIT's 10th president, James Rhyne Killian Jr. I often passed through this location when running along the Charles River. I had this sketch on the back-burner for a while now, and by chance I decided to prepare it for this Tuesday, exactly three years after the last time I met with Patrick. ↩

Winston, Patrick H. Holmes, Dylan. The Genesis Manifesto: Story Understanding and Human Intelligence. 2017. ↩

Patrick Winston and his students formed The Genesis Story Understanding Group. ↩

As described in this article in the NVIDIA blog (July 29, 2016), narrow artificial intelligences are "technologies that are able to perform specific tasks as well, or better than, we humans can." ↩

Suggestive Drawing Among Human and Artificial Intelligences (May 2017) was my master's thesis at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, in which I explore the role of machine learning in design or, more specifically, in drawing. ↩

On April 29, 2020, Patrick's colleagues, students, friends, and acquaintances were invited to join PHWFest, a gathering to share memories and experiences, an event that has been postponed due to the current COVID-19 situation in Boston. ↩